Do all entertainers benefit from the Future of Where? Or only Taylor Swift?

Last week I said we're seeing a remarkable comeback in in-person activity thanks to sports and entertainment -- and that may be the future of where. But not all entertainers or athletes may benefit.

Although this post is free, The Future Of Where depends on your support to continue. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber!

Last week’s entry (“Taylor Swift Is The Ultimate Pop-Up Business”) generated a lot of interest – including further evidence of my argument and a strong opinion that I’m not as right as I think I am.

My general thesis, based in part on the overwhelming economic power of Taylor Swift’s Eras tour, was that in the post-pandemic world we’ll still see a lot of in-person activity. But it’ll be different than before, focused much more on special events (especially sports and entertainment) and much less on day-to-day commuting and errands.

Taylor Swift’s Eras tour generated at least $5 billion in economic activity

It builds on my underlying assumption about the “future of where” – that future in-person interaction will depend on compelling experiences that bring us together because we want to be together, not because we have to be in the same place.

Further evidence that I might be right comes from Page Forrest of Pew Trusts, who wrote a blog, interestingly enough, titled “Stadiums, Nightlife, and Taylor Swift: Cities and States Are Banking on Busy Weekends”. The blog pointed to a variety of data sources suggesting that activity in downtowns on weekends and weeknights is now higher than during the workday. People are looking to downtowns and other activity centers for fun, not work. Page also pointed to a Washington Post article suggesting that, post-COVID, people are saving less and spending more on “YOLO” (You Only Live Once) Experiences. She also pointed out that there’s been a new rash of public financing of stadiums to tap into the YOLO economy.

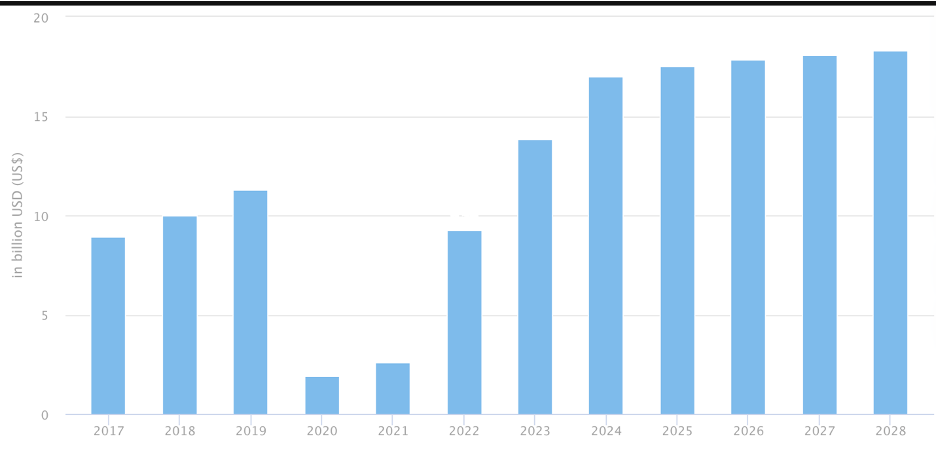

Meanwhile, Statistica provides further evidence that in-person music experiences are on the reise. Statistica estimates that music events now generate $17 billion per year, compared with only about $12 billion in 2019. Per-person spending on music events is also on the rise, now exceeding $220 per person.

Live Music Event Revenues By Year

Source: Statistica Market Insights

But think about it

$17 billion per year, of which $5 billion is Taylor Swift? (I admit this is an approximation derived from two very different data sources, but still.) Is everybody benefiting from the live entertainment and sports boom? Or only the big stars?

One of my readers weighed in strongly on this question, saying only the stars benefit. “Please check in with the second tier bands and ‘smaller venues’ (like the popular 930 Club/an IMP venue), in DC and assert your same argument to them,” he said. “I believe they would read you the riot act. The concert business (second tier) isn’t unlike restaurant dining (or outdoor dining which were allowed to encroach into streets in many, if not most cities) or for that matter anything else that is social (draws people together). We are still in recovery mode, and some aspects of the Covid lockdowns (maybe just subconsciously) look to be at least a little longer lasting or more permanent to date.”

The legendary 9:30 Club in DC

That’s a fair point. Is the pent-up demand only for the Taylor Swifts of the world? And bigtime professional sports? While second-tier sports and entertainment still suffers? Major-league baseball attendance is up compared to 2019, but minor-league baseball attendance is still down from pre-pandemic levels, even accounting for the fact that organized baseball eliminated some minor-league teams after the pandemic.

Interestingly, as the Pew blog suggests, cities may not care. Big-time events in big venues may generate enough economic activity – and tax revenue – that mayors and city bureaucrats are happy. But it’s probably true that those of us who care about cities and towns have a lot of work to do in getting people out of their homes to see entertainers who aren’t Taylor Swift and sports teams that aren’t the Yankees or the Dodgers.

We’ll be taking next week off, returning on January 6th.

The ABBA Voyage experience in London offers an interesting counterpoint to the Taylor Swift phenomenon while reinforcing your core thesis about the future of in-person entertainment. While Swift generates billions through traditional touring, ABBA has innovated a new model that generates approximately $5.2 million per month through their avatar-based concert venue, which runs multiple shows daily since May 2022. The "concert" creates a novel hybrid between a traditional concert experience and immersive entertainment that is so fun (I've been).

This format solves several issues you've highlighted: it's a sustainable "pop-up" business model that can run indefinitely, it creates consistent economic activity for its location (unlike one-off tour stops), and it demonstrates how established artists can monetize their brand without the physical demands of touring. The fact that fans repeatedly return to see the same show suggests that, like Swift's Eras Tour, it's not just about the music—it's about the shared experience.

ABBA Voyage might actually point to a third way in your "superstar vs. smaller venue" dichotomy. It shows how legacy acts can create compelling in-person experiences that drive consistent economic activity without requiring actual touring infrastructure. This could become a template for how other major artists transition from traditional touring while maintaining the kind of "special event" draw you describe as crucial to future urban activity.