Factory towns in the U.S. have been coming back. Tariffs won't help them.

Places like my hometown have spent decades climbing out of an economic hole created when big factories closed. But their revived manufacturing economies will suffer from Trump's new tariffs.

As I explained in my book Place and Prosperity, when I was a kid I lived in what I thought was a very provincial town – Auburn, a small factory town in Upstate New York where, it seemed to me, nothing ever changed. Nobody ever moved in our out of town and everybody stuck to their own neighborhood based on ethnicity or economic class. Except for college, my father literally never lived or worked anywhere more than a mile from where he grew up until he was in his 50s.

But in fact this provincial little town was deeply connected to the rest of the world by trade.

Posts like these are made possible by The Future Of Where’s paying subscribers. Consider becoming a free or paid subscriber today!

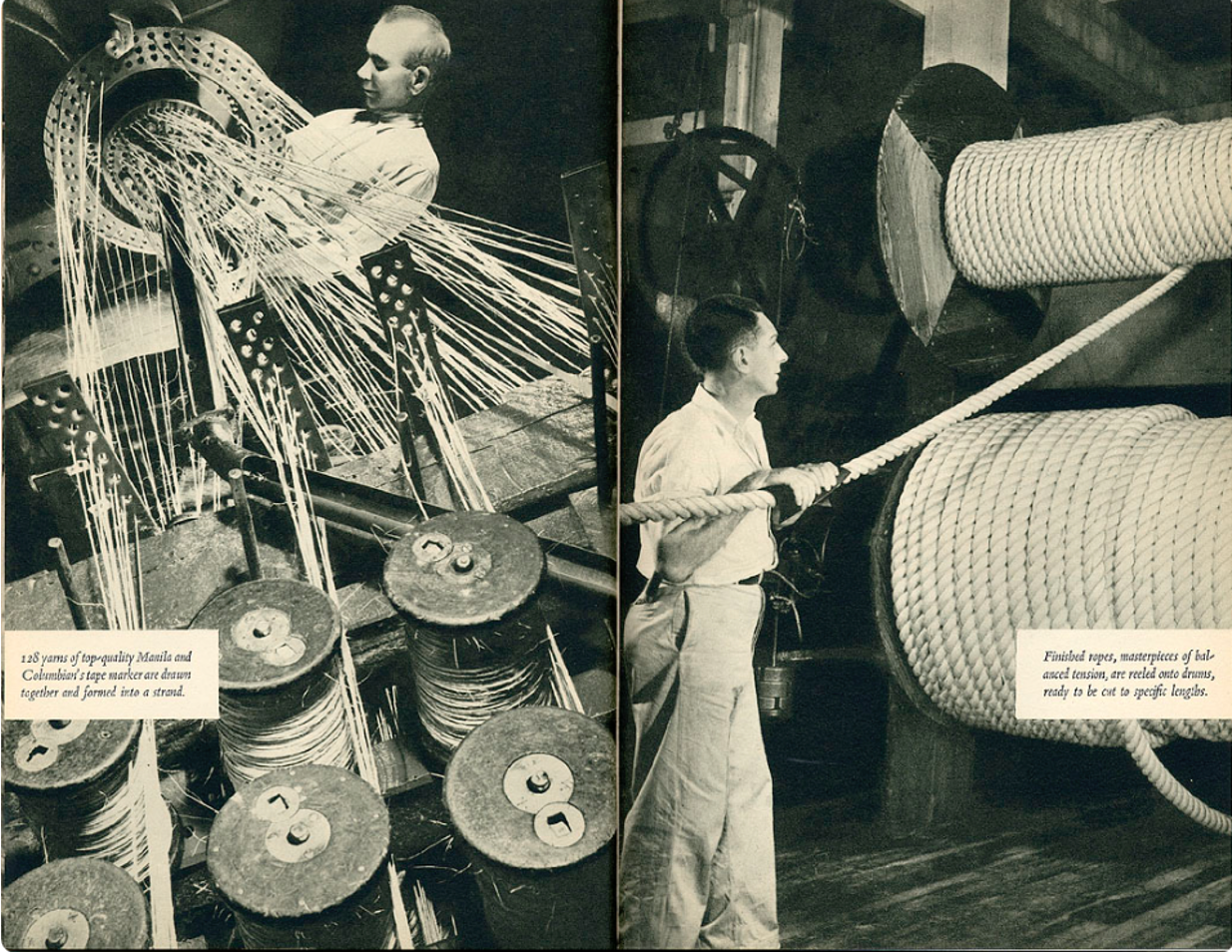

The largest and most successful manufacturing company in town was Columbian Rope Company, one of the largest rope companies in the world, where my grandfather, who was a chemist, worked as head of the R&D lab. Columbian Rope employed several generations of townsfolk as factory workers, giving the small city a sense of economic security that many factory towns felt because their large factories hummed 24/7.

The beautiful process of manufacturing rope in my hometown required Manila Hemp from the Philippines.

Columbian Rope was deeply connected to the rest of the world. The company scoured the world for raw material, especially in the Philippines, where the Abaca plant provided what came to be known as “Manila Hemp”. (In fact, the guy who lived across the street from us, who worked at Columbian Rope, had been interned by the Japanese in Manila all during World War II.) Manila Hemp and other raw materials were imported to my provincial hometown and manufactured into rope in Columbian’s beautiful factory, where twine literally wound around the entire rectangular building to make rope. Then the rope was sold all over the world.

Columbia didn’t last forever, of course. Around 1980 the prominent local family that owned the company sold it to a rope company in the South, where only remnants of it remain today. The beautiful factory closed and was torn down to make way for a shopping center. And my hometown went into tailspin that lasted for a couple of decades at least.

Economies Are Regional, Not National

I bring up the story of Columbian Rope because at the moment trade is the most important issue in the country. President Trump’s tariffs are deliberately designed to disrupt the worldwide system of importing and exporting raw materials and goods – apparently with the hope that manufacturing will move back to the United States from overseas.

But the thing to remember is that trade is essential to the prosperity of any city or town, like the one I grew up in. The whole basis of a town’s prosperity is based on traded goods and services – the very processing of selling to people elsewhere things you find or create locally. When I ran a small research and consulting business in Ventura, California, I used to say that my real business was importing money into Ventura. A city or foundation somewhere else would pay my company money, and the folks I worked with would then create some report or policy initiative that we would then export back to them. The money stayed in Ventura, helping the city to prosper.

Trump’s view appears to be that a trade deficit with any country is bad for the United States. Any time we give more money to another country than they give to us, we’re getting the short end of the stick.

But for a city or town – or even a metropolitan region – whether you are trading goods and services with Los Angeles, London, or Lesotho doesn’t really matter. Because economies aren’t national or even statewide. They’re regional. What’s important is that you are trading goods and services with people and companies somewhere else. That’s how money flows into your local economy, and that’s what forms the foundation of prosperity in a particular place.

In fact, international trade has been essential to America’s prosperity since the beginning. Maybe you’ve been to Cooperstown, the charming 18th Century town in Upstate New York that’s home to the Baseball Hall of Fame. But what you may not know is that Cooperstown owed its early prosperity to potash.

The charming settlement of Cooperstown was originally built on exporting potash that local residents created by burning trees.

Early Cooperstown landowners had no way to pay off land speculators through farming or commerce. So they burned the trees on their property to make potash – a key ingredient in soaps and other manufactured goods made in Europe. So the potash was exported to Europe and the manufactured goods were imported back to America (as well as other places). And Cooperstown thrived. (This story is masterfully told in historian Alan Taylor’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book, William Cooper’s Town. William Cooper was the founder of Cooperstown and the father of author James Fenimore Cooper.) Eventually, of course, the U.S. built up its own manufacturing industry and trade began to flow in both places. (Interestingly, the other day Trump reduced his proposed tariff on Canadian potash imports to the U.S. after getting pushback.)

The Big Factories Are Not Coming Back

The other day on X (Twitter), somebody sympathetic to MAGA posted a photograph of the Packard plant in Detroit in 1956, at the time it closed, and said, “I am for tariffs because I want this back”. Packard at one time employed as many as 40,000 people – mostly men – at the plant, just as Columbian Rope once employed thousands of men working the rope manufacturing line in my hometown of 30,000 people.

The Packard plant in Detroit, which once employed 40,000 people and was eventually torn down in pieces.

But the fact of the matter is that the Packard plant of 1956 – or the Columbian Rope plant of my childhood – is never coming back, for the simple reason that manufacturing is now automated. Yes, there is more manufacturing in China and Mexico than there used to be. There is also more manufacturing output in the United States than ever before.

But there are fewer manufacturing jobs everywhere in the world than there used to be, including in China. And with the increasing use of robots in factory floors, there will be fewer and fewer manufacturing jobs in the future even as we manufacture more stuff.

Trying to bring more manufacturing back to the United States in order to generate jobs is like trying to bring foreign agriculture back to the United States in order to create more jobs for farmhands. You can bring the activity back, but the jobs just aren’t there. Instead of thousands of laborers on a factory floor, you’ve got hundreds of people watching computer screens monitoring a bunch of robots.

What’s gotten lost in all this debate about tariffs and trade is that “re-shoring” of American manufacturing is already occurring, and many cities and towns with a manufacturing history are already benefiting.

Tariffs Will Hurt Our Reviving Factory Towns

A couple of years ago I gave a speech in my hometown about economic development. In preparation for that speech, Brookings Metro kindly ran some numbers about the economy in my home county of Cayuga County, N.Y., in the Finger Lakes between Syracuse and Rochester. And what Brookings found was astonishing: Between 2010 and 2021, the manufacturing output of the county more than doubled. The output in other private industry increased only 20%.

What factories in my hometown look like today.

And it’s not just one big factory. It’s lots of small entrepreneurs, in a town with a history of making things, starting up manufacturing businesses and finding markets all over the country and all over the world.

So my fear for towns like Auburn is that the traded economy – the lifeblood of any community’s prosperity – will suffer because of the tariffs. Trump is hoping that trade just gets redistributed – that it mostly stays in our country rather than going back and forth between other countries. But in all likelihood, overall trade will go down.

And unfortunately that will teach us all the lesson of Place and Prosperity anew: traded goods are the basis of a place’s prosperity; traded economies are regional and not national; and prosperity comes from win-win trading, not from the kind of zero-sum game Trump prefers.

Your terrific post caused me to ask Microsoft's AI bot, Copilot, to compare the total value of U.S. manufacturing output from 1964 to 2024. Here is a summary of what Copilot provided. If you'd like the longer version, just let me know -- pike@urbanexus.com.

1964 (in 2024 dollars): Approximately $1.9 trillion in manufacturing output.

2024: Approximately $4.0 trillion in manufacturing output.

This shows that even though manufacturing’s relative share of GDP has declined over the past 60 years, its real (inflation-adjusted) output has more than doubled, driven by higher levels of efficiency, larger-scale production, and the overall expansion of the U.S. economy.

Labor hasn't fared as well. Manufacturing employment declined from about 16 million workers in 1964 to around 12.8 million in 2024.

Most of today's manufacturing in the U.S.A. depends on supplies and components sourced internationally. If maintained, the Trump tariffs will likely significantly and negatively impact what we produce in the U.S.A.leading to job losses in that sector.

Coming from an urban planning background I’m curious what your thoughts are on Jane Jacob’s theory that metro regions are the main economic drivers of prosperity and that they should be focused on import replacement. Is that region relevant or are you thinking regions of the country or regions of the world?