Is Any Where Safe, Part 3: Where Will People Go?

The bottom-line question is this: If people are displaced, is there a place for them to relocate to?

As those of us in Southern California continue to reel from January’s devastating fires in Pacific Palisades, Altadena, and elsewhere, I ran across a really interesting set of statistics from the Census Bureau (assuming the data is still online).

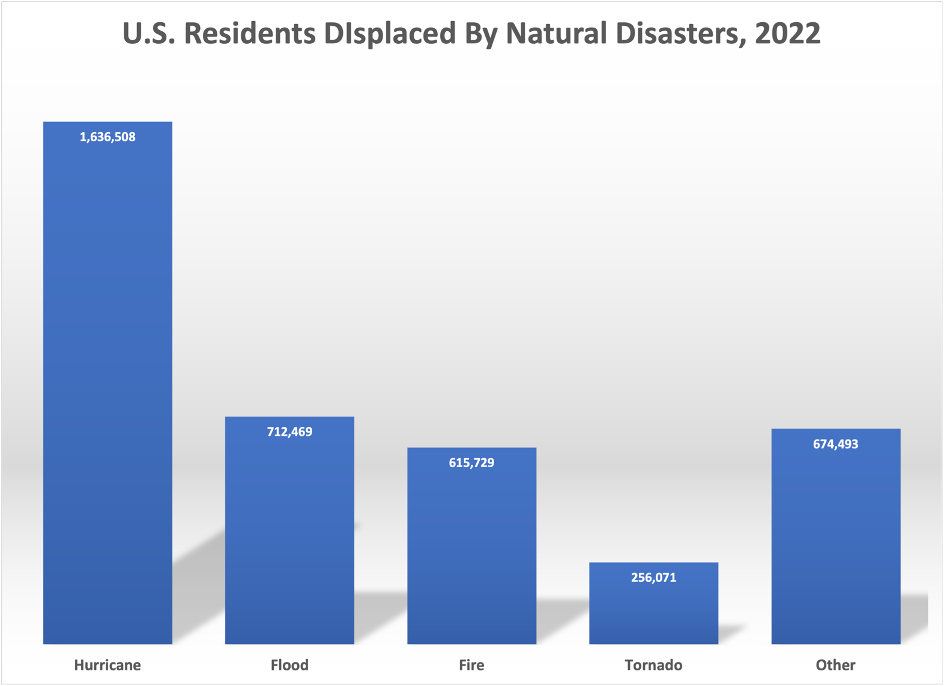

In 2022, more than 3 million people in the United States were displaced from their homes by natural disasters. That’s 1% of our national population. Half of the displacements were the result of hurricanes. And by the end of that year, 600,000 people were still out of their homes.

Although this post is free, The Future Of Where depends on paying subscribers to continue bringing you great content. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber today!

There’s been a lot of debate since the L.A. fires – some of which I have been involved in – about whether the L.A. neighborhoods should be built back exactly as they were before or whether they should be built back in some different way. (So far, California Gov. Gavin Newsom has made it easier to build back the same thing but not something different, which is the norm in these situations.)

Who Will Be The Climate Refugees?

But what happens if people can’t – or can’t afford to – move back to the homes and communities lost to fires, hurricanes, rising sea levels, and other natural hazards? Will they simply become “climate refugees”? And what kind of additional pressure will that put on our already overpressured housing market, not just in California but everywhere in the United States?

We often focus on the can’t but I think we also need to pay attend to the can’t afford to. Longtime residents of a neighborhood are often under-insured, which means they can’t always build back even if regulatory pressures are eased. This is a particular problem in areas where home prices have risen dramatically in recent years. (It’s not surprise that median home price in Pacific Palisades is $3.5 million, but it’s important to note that even in supposedly middle-class Altadena, median home price before the fire was $1.3 million.) There are going to be a lot of people – many of them older and not that well-off – who are going to lose their homes to disaster and will be unable to build back.

There’s been a lot of speculation about what you might call long-range climate refugees – people who will find 115-degree weather in Phoenix or constant hurricanes in Tampa unbearable and will move to the north (or back to the north) as the winter weather in Chicago or Minneapolis becomes more temperate.

That may be a long-term trend based on what you might call chronic conditions in the South and Southwest.

But I don’t think most people with what you might call acute problems – their house destroyed by a fire or a hurricane – are going to want to move long distances, especially if they are older or have modest incomes. They’re going to want to stay close to where they lived because of jobs, family, and connections.

Help us grow our audience by sharing this post with those who may be interested in it.

So where do they go?

That’s a tough question to answer. If they’re lucky, they’re homeowners who will be able to sell their property for something – even if they can’t afford to rebuild – and find some living situation somewhere in the region where they want to live. But that assumes that the neighborhood they used to live in will continue to exist, at least for the purposes of selling their property.

Increasingly, I think, cities and counties will face the increasingly tough question of whether to allow people to build back at all. Yes, in the case of wildfires anyway, new construction is likely to be more fire-resistant then houses that are decades old. But there may come a point in many cases where it is more expensive to taxpayers (and insurance policyholders) to keep allowing rebuilding than to buy people out.

We already see this in flood-prone Houston, where the Harris County Flood Control District has increasingly bought out repeatedly flooded properties (on a voluntary basis, with both federal funds and local funds). Is there any reason we should see similar programs involving properies up against the canyons in L.A.?

Harris County (Houston) has an increasingly important buyout program.

The most dramatic example of buyout and relocation in the United States right now is Isle de Jean Charles in southern Louisiana. In that case, however. it’s not that the location is dangerous. Rather, the location is going away. As the sea level rises, many islands in southern Louisiana are disappearing and Isle de Jean Charles is no exception. The last few hundred residents are being relocated a “New Isle” 40 miles away, at a cost of $50 million in federal money.

Mandatory relocation is politically difficult; after all, nobody wants to leave the home or neighborhood – or their ability to sell their ravaged property to start a new life. So government at all levels will have to find ways to pay for relocation: bonds issued by the city or county, state or federal grants, insurance surcharges, maybe even transfer of development rights programs (which are notoriously tricky to make work). All this is extremely expensive, however. If it costs $50 million to move a few hundred people, how much will it costs to move a whole community?

Isle de Jean Charles is literally disappearing

And both the local governments and the residents themselves will have to make difficult choices about where and how to live. If you take away single-family homes in a flood-prone or high-fire-risk area, presumably you’ll have to concentrate more development on less land. That means if displaced residents want to stay in their neighborhood, they have to accept a different type of housing and a different lifestyle.

Or I may be wrong and an increasing number of people will just leave for good. We saw this during the pandemic, when many of those who could flee expensive metropolitan areas did so and settled in smaller communities far from their traditional roots.

Whatever decision people make, our communities are likely to change significantly. And I think that’s the lesson of the last few disaster-ravaged years (including the pandemic): You can’t freeze-dry a town, and you certainly can’t just keep rebuilding a town over and over again. Towns have to be adaptable, flexible, resilient – and though it’s difficult, people do too.

In other news: Goodbye to Don Shoup

Like many urban planners, I am deeply saddened by the passing of my former professor, UCLA’s parking guru Donald Shoup. So I wrote a piece that’s both an appreciation and a remembrance, which we put in front of the paywall at California Planning & Development Report.

A few interesting articles about the causes of wildfires:

Mike Davis | Ecology of Fear | Metropolitan Books | September 1998

The Case for Letting Malibu Burn

Many of California’s native ecosystems evolved to burn. Modern fire suppression creates fuels that lead to catastrophic fires. So why do people insist on rebuilding in the firebelt?

(Extract)

“Less well understood in the old days was the essential dependence of the dominant vegetation of the Santa Monicas—chamise chaparral, coastal sage scrub, and live oak woodland—upon this cycle of wildfire. Decades of research (especially at the San Dimas Experimental Forest in the San Gabriel Mountains) have given late-twentieth-century science vivid insights into the complex and ultimately beneficial role of fire in recycling nutrients and ensuring seed germination in Southern California’s various pyrophytic flora. Research has also established the overwhelming importance of biomass accumulation rather than ignition frequency in regulating fire destructiveness. As Richard Minnich, the world authority on chaparral brushfire, emphasizes: “Fuel, not ignitions, causes fire. You can send an arsonist to Death Valley and he’ll never be arrested.”

A key revelation was the nonlinear relationship between the age structure of vegetation and the intensity of fire. Botanists and fire geographers discovered that “the probability for an intense fast running fire increases dramatically as the fuels exceed twenty years of age.” Indeed, half-century-old chaparral—heavily laden with dead mass—is calculated to burn with 50 times more intensity than 20-year-old chaparral. Put another way, an acre of old chaparral is the fuel equivalent of about 75 barrels of crude oil. Expanding these calculations even further, a great Malibu firestorm could generate the heat of three million barrels of burning oil at a temperature of 2,000 degrees.

“Total fire suppression,” the official policy in the Southern California mountains since 1919, has been a tragic error because it creates enormous stockpiles of fuel. The extreme fires that eventually occur can transform the chemical structure of the soil itself. The volatilization of certain plant chemicals creates a water-repellent layer in the upper soil, and this layer, by preventing percolation, dramatically accelerates subsequent sheet flooding and erosion. A monomaniacal obsession with managing ignition rather than chaparral accumulation simply makes doomsday-like firestorms and the great floods that follow them virtually inevitable.”

Another article:

Reason Magazine

California's Fire

Catastrophe Is Largely a

Result of Bad

Government Policies

This year's deadly wildfires were predicted and unnecessary.

J.D. TUCCILLE | 1.13.2025

(Extract)

"Proactive measures like thinning and prescribed burns can significantly reduce wildfire risks, but such projects are often tied up for years in environmental reviews or lawsuits," Shawn Regan, vice president of research at the Montana-based Property and Environment Research Center (PERC), told me by email. "In places like California, these delays have had devastating consequences, with restoration work stalled while communities and ecosystems burn to the ground. Addressing the wildfire crisis will require bold policy changes to streamline reviews, cut red tape, and ensure these projects can move forward before it's too late."

For example, as I've written before, under the requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), members of the public and activist groups can formally object to proposed actions, such as forest thinning, through a bureaucratic process that slows matters to a crawl. If that doesn't deliver results, they move their challenges to the courts and litigate them into submission. The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) creates additional red-tape hurdles at the state level, imposing years of delays.

Regan and his colleagues at PERC have frequently addressed this subject-presciently, you might say, except that everybody except California government officials saw this moment coming.

California has failed to effectively manage its forests. "Decades of fire suppression, coupled with a hands-off approach to forest management, have created dangerous fuel loads (the amount of combustible material in a particular area," Regan wrote. Ominously, he added: "With conditions like this, all it takes to ignite an inferno is a spark and some wind."

In 2020, Elizabeth Weil of ProPublica also named California's forest management as a serious concern.

"Academics believe that between 4.4 million and 11.8 million acres burned each year in prehistoric California," Weil noted. "Between 1982 and 1998, California's agency land managers burned, on average, about 30,000 acres a year. Between 1999 and 2017, that number dropped to an annual 13,000 acres." She emphasized that "California would need to burn 20 million acres—an area about the size of Maine — to destabilize in terms of fire.

In 2021, Holly Fretwell and Jonathan Wood of PERC published Fix America's Forests: Reforms to Restore National Forests, recommending means to address wildfire risks in California and across the country. To claims that the wildfire problem is overwhelmingly one of climate change, they respond that a "study led by Forest Service scientists estimated that of four factors driving fire severity in the western United States, live fuel 'was the most important,' accounting for 53 percent of average relative influence, while climate accounted for 14 percent." Climate matters, but other policy choices matter more.

Fretwell and Wood recommend restricting the scope of regulatory reviews that stands in the way of forest restoration, requiring that lawsuits against restoration projects be filed quickly, and excluding prescribed burns from carbon emissions calculations that can stand in the way of such projects.

"There is broad agreement on the need for better forest management, but outdated policies and regulatory hurdles continue to delay critical restoration efforts," Regan told me.

If government officials finally take these hard-learned lessons to heart and ease the process of providing and storing water, restoring forests, and fighting fires, Californians might be spared from future disasters. They seem poised to work with the incoming Trump administration on exactly that. But reforms will come too late for those who have already lost lives, homes, and businesses.”

A final article:

This is an extract from a January 10, 2025 National Review article by Ryan Mills that explains much about the causes of the devastating LA fires:

“And while the topography is different - the fires around L.A. are burning the chaparral landscape in the mountains and foothills around the city, not in forests — the lesson is the same, said Edward Ring, director or water and energy policy at the conservative California Policy Center: The L.A. fires have gotten out of hand largely due to poor land management.

"Historically, that land would either be deliberately burned off by the indigenous tribes or it would be grazed or it would be sparked by lightning strikes," said Ring, an advocate of continuing to manage the chaparral land's oaks and scrub brush with grazing animals, mechanical thinning, and controlled burns.

But that hasn't happened, he said, due to public policies, bureaucratic resistance, and pushback from environmental activists. The result: The L.A. foothills were primed to burn.

But Ring and others say the biggest problem that has allowed the fires to do as much damage as they have is tied to a lack of land management in the L.A.Basin. He blames the problem on state and local government bureaucracies, lawmakers in the pocket of environmentalist and renewable energy lobbyists, and legal challenges from activist groups that can grind the ability of landowners to manage their property to a halt.

Environmental groups, including the California Chaparral Institute, the Sierra Club, and the California Center for Biological Diversity, have aggressively fought against thinning and burning that state's chaparral landscape. In a 2020 letter to lawmakers, they argued that "adding even more fire to native chaparral shrublands" is not an acceptable policy.

"They make it virtually impossible to do controlled burns of any kind. They make it virtually impossible to do mechanical thinning. And they make it very difficult and in many cases impossible to even have grazing on your property," Ring said.

"Everything requires an environmental impact statement, and everything requires permits from the [South Coast] Air Quality Management District," he continued. "All of these things are just impenetrable bureaucracies. They just tie everybody up in knots."

Ring said a focus on single-species management, rather than total-ecosystem management, makes it easy for environmentalist lawyers to find a single bird or lizard that could be affected by a land management project to put the project on hold.

"The Endangered Species Act and the California Environment Quality Act have both turned into monsters that have not only prevented any kind of rational land management, but they've actually had the perverse, opposite effect in many respects," he said.”

This is an incredibly complex issue. I keep coming back to the mixed and black neighborhoods in Altadena where often the only generational wealth was in the homes bought decades ago. Many were under-insured. If we can creatively come up with solutions for those neighborhoods we will have some formulas that could help elsewhere.