The 15-Minute City Is Great For Those Who Can Afford It

But most people who work in a 15-minute neighborhood can’t afford to live there. We have to build more 15-minute neighborhoods to meet demand and make sure at least some housing in them is affordable.

I live in a classic 15-minute city.

The 15-minute city encompasses the idea that if you live an urban life, you should be able to reach any destination you want within 15 minutes, preferably on foot. Although some conspiracy theorists seem to think it’s a veiled attempt to create urban concentration camps, many urbanists see it as no less than the urban ideal. And I am lucky enough to live this ideal.

Though this post is free, The Future Of Where is brought to you by paying subscribers. If you like this content, help us keep it going by becoming a paying subscriber today!

We take the car out maybe once or twice a week. It’s a 10-minute walk to the supermarket (with another even closer on the way). My optometrist is a 5-minute walk; the UPS store and my bank are literally across the street from where I live. My office is a 20-minute walk or a 10-minute light-rail ride. From my place I can easily walk across the street to the train station, from which I can take trains and buses almost anywhere in San Diego and Southern California, including the airport, which is a 10-minute bus ride away. Two of our major music venues are also walkable. It’s even a short walk to our local ferry terminal. And that’s not including the dozens of bars, restaurants, and coffee shops in close proximity to where I live. The other day I got called for jury duty – and the courthouse is four blocks away.

Pedestrians walk past the entrance of the U.S.S. Midway Museum near where I live.

So the 15-minute city works for me. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work for almost everybody who works in the neighborhood.

The bare minimum for rent in this neighborhood is $4,000 a month. That’s a thousand more than would be affordable to a household making San Diego’s median income, and double what’s affordable to two service workers making $20 an hour, which is probably typical in the neighborhood.

The bare minimum to buy anything is $800,000, with most places going for over $1 million. That’s just out of reach for anybody working in the neighborhood.

So all the time, you see ordinary folks working in 15-minute cities who are seriously inconvenienced because these neighborhoods are crowded and expensive. Many workers have to walk a long distance or even take transit to get from their car to their workplace. (In a neighborhood where another high-rise is always going up, I see construction workers all the time on the train and walking down the street.) And people often have to commute long distances to work in a 15-minute city; in my neighborhood, service workers often live in Tijuana and endure a commute of an hour or more, crossing an international border, to their jobs nearby.

Many people prefer to live far away from their jobs or in suburban locations, and that’s fine. Lots of San Diego workers who live in Tijuana do so because it is so much less expensive and that makes sense too. (And obviously most service workers generally have to work onsite and can’t work remotely.) But the evidence suggests that lots of people who work in a 15-minute city would like to live in one too, but they can’t simply can’t afford it.

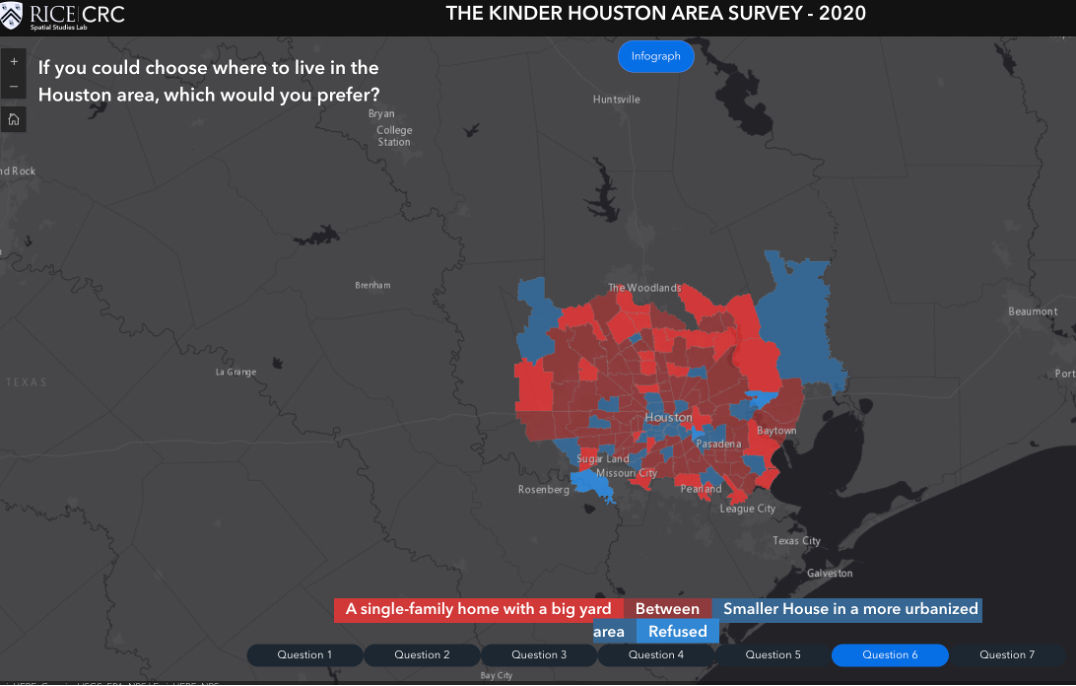

This map from the Kinder Institute’s survey shows that those who live farthest from the center are the ones most interested in licing in a 15-minute city.

The best way to grow The Future of Where’s audience is for you to share these posts with people you know. Please share this post with those who might find it interesting.

Why Are 15-Minute Cities So Expensive?

There are two basic reasons why 15-minute cities are so expensive.

The first is that neighborhoods that have lots of things people want – so-called “high amenity” or “high resource” neighborhoods – are always going to be more expensive than other places. No matter whether it’s a walking neighborhood or a driving neighborhood, if people can live close to things they want – to some it will be work, to others it will be nature trails, for still others it will good a good school – they’ll pay more for it. That prices other people out.

The second is that we simply haven’t built enough 15-minute neighborhoods in the United States. Most public opinion surveys find that about half of American’s would prefer to live in a smaller house in a more walkable neighborhood. (And take a look at this map on that question from the Kinder Houston Area Survey: that desire is strongest in the exurbs.) But most of what we build in the United States is suburban in nature – even townhomes and apartments in suburban locations are usually built around the automobile. Scarcity always drives prices up, and a scarcity of neighborhoods with the features people want is no exception.

How Can We Make 15-Minute Cities More Affordable?

As with so many other problems in our country today, this pretty much comes down to housing supply and affordability.

First, the supply side, which is an easier question. We simply need to build more housing in the United States, period, and more of it needs to be located in 15-minute neighborhoods. This doesn’t necessarily mean that all new housing has to be located in existing neighborhoods. After all, most new housing built in the United States is built in greenfield locations. But those greenfield locations need to have more 15-minute aspects to them – as, increasingly, suburban town centers do indeed have.

The Town Square plaza in suburban Sugar Land, Texas

Some developers of suburban master-planned communities have figured this out, essentially switching from communities that revolve around golf courses to communities that revolve around town centers. But it’s not the norm, and most suburban developers just want to build what they know how to build, which usually means carpetbombing a greenfield site with a bunch of houses.

A typical new suburban neighborhood in Celina, Texas, north of Dallas, the fastest-growing city in the country.

That’s why 15-minute suburban neighborhoods actually requires the public sector to do real planning as well – and sometimes to invest at the front end in infrastructure and facilities. In other words, sometimes the local city or counties has to serve as the master developer in order for suburban 15-minute neighborhoods to come about.

Housing affordability is a much trickier problem, for the very reason I mentioned above: Affluent folks bid up the price of high-amenity neighborhoods. I have struggled for my entire career about how to deal with this problem.

On the one hand, I believe strongly that the private building industry can provide a lot more housing – at scale – than the government or the nonprofit sector will ever be able to do.

On the other hand, private real estate development in a desirable urban neighborhood tends toward higher-density and higher-cost housing. My neighborhood used to have a wide variety of low- and mid-rise housing, but now all anybody builds is high-rises with million-dollar condos and $6,000-a-month apartments. Which means that, like it or not, some housing in a neighborhood like mine has to be income-restricted, in order to maintain diversity and give folks who work here a chance to live here.

Little Italy in San Diego near where I live. The older buildings are varied in their density but the new construction is all high-rise.

Affordable housing developers do noble work, though they understandably tend to focus on the lowest-income folks and they will never build enough housing to provide housing for everybody. (An affordable housing developer I talked to once said, “I know that all I’m doing is creating lottery winners.”) Which is why it seems to me that, if you want to build middle-income housing for folks who work in a 15-minute neighborhood, it’s got to be partly up to the employers to do it.

Employers typically don’t care where their employees live and are perfectly willing to let their workers bear the burden of commuting. But employers do have an interest in ensuring that they have an available workforce in the general vicinity; otherwise they can’t do business. While individual employers may sometimes be able to, say, subsidize apartments for their employees, it’s not realistic to expect them to go into the real estate development business. But they could invest in housing impact funds to buy or build affordable housing near their locations, with some units set aside for their employees.

The 15-minute city isn’t for everybody (especially conspiracy theorists). But we should make sure that there are more of them around and that they can truly welcome everyone, including the people who work in them.

And if you are an AICP planner in need of Certification Maintenance credits, please consider taking one of my one-hour, on-demand courses. Current topics include finance for planners, economic development, and parking. Click here for more details.

I am trying to understand the fullness of your point. I do believe this is a supply problem; in my mind there is no doubt. And I'm not sure I see how taxing the landowners would bring prices down. They would bring land costs down, but landowners back into the land cost, so it would probably be a wash.

You didn't say anything, Bill, about the retail component of 15-minute cities. I'm a retail planning and real estate consultant, and I have been going back and forth with a current client (in a part of the world you know well), the City of Ithaca, which admirably wants to "plan for the city that [it] aspires to" -- with a 15-minute Downtown that includes its own supermarket -- to which I have to tell them that it is not all that likely, for a whole host of reasons. For one thing, major grocers in this country - like Wegmans - put little to no brainpower into a truly urban format (and 88K sq ft in Astor Place does not count). And if/when they do, they focus primarily on the largest, most dense cities, not vibrant yet modestly-sized Downtowns like Ithaca's, where more car-friendly sites are available in close proximity (in this case, along NY 13).

It is no surprise that the 15-minute concept first gained traction in Europe, where the mainstream retail industry orients much more towards urban settings. Alas, North America is a very different animal...