The Politics Of Where

Increasingly, our politics are determined by where we live. But will it last? Or will that change as the political landscape shifts?

Not everybody likes the idea of the 15-Minute City.

Where is embedded in our political system – and it has increasingly become quite literally a map of our partisan divide.

Take last week’s presidential election, for example. Although we decide who’s president based on which candidate wins states, all the media coverage – all those “magic walls” on CNN and other networks – weren’t really about states. They were about counties – who was winning which county, whether turnout was high in urban counties, whether Kamala Harris could cut into Donald Trump’s margin in rural counties (which, obviously, she didn’t).

Part of the reason for this approach is that our elections are run at a county level and therefore data at that level is easy to come by. But it also reveals our nation’s stark partisan divide.

The Where Of Politics

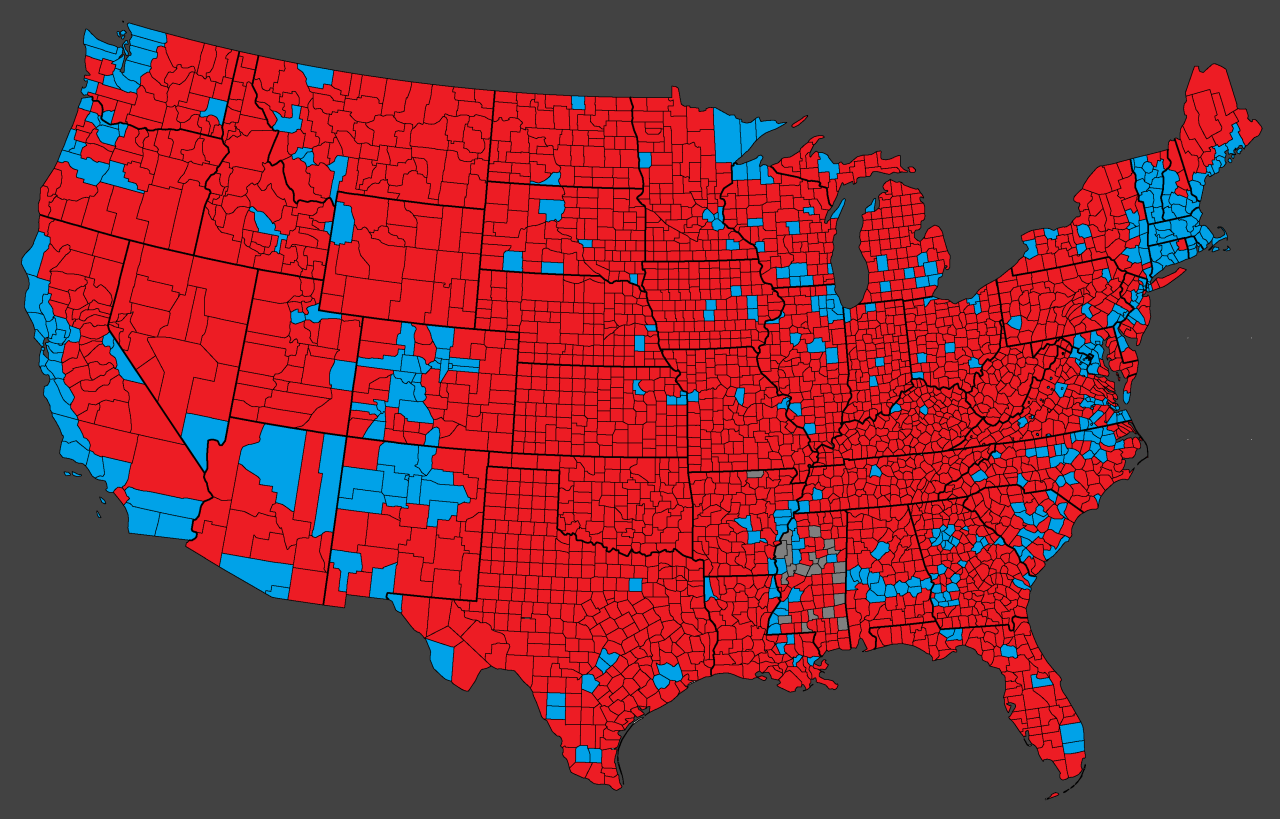

Take a look at this map of last week’s election results by county. Anywhere there’s a city – a dense population center – you see blue. Everywhere else you see red.

The role that “where” plays is obvious in this county-level map of presidential results

In other words, as Bill Bishop and Robert Cushing first explained almost 20 years ago in The Big Sort, we are increasingly sorting ourselves geographically by our cultural and political beliefs.

It’s the nature of the real estate industry that people sort themselves geographically by economic class and often by race. You can only live in neighborhoods you can afford, and if you’re not white, historically you’ve been shut out of certain neighborhoods.

But the sorting by political belief – and by backgrounds that drive that belief – is relatively new. As Bishop and Cushing wrote in The Big Sort, a half-century ago college-educated people were scattered evenly across the landscape. Now they are concentrated in cities and inner suburbs. They have congregated in specific communities that have specific characteristics. The same is true of people without college educations who tend to live in exurbs and rural areas.

This geographical sorting reflects the cultural divide that currently characterizes our nation. Walkable, amenity-rich urban areas have become a kind of luxury consumer item, especially for Democrats. Meanwhile, auto-bound suburbs and exurbs have become the preferred destination for Republicans – at least for white Republicans. And it’s increasingly dangerous for to “cross the line” – as the story I told last week about urban bicyclists getting hammered by “rolling coal” in the exurbs suggests.

The Politics of Where

But even as we are sorting ourselves geographically by our politics, we are also shaping our politics based on where we sort ourselves geographically. And this has a profound effect on how we view each other and whether we trust each other.

When people of different political beliefs live and work in close proximity to one another, they get to know each other as people. When they are separated by geography, they know each other only indirectly – increasingly through hostile media and social media interaction – and they are less likely to trust each other. (The subtitle of The Big Sort, by the way, is Why the Clustering of Like-Minded America is Tearing Us Apart.)

And, frankly, both sides are pretty smug about where they live.

Urban Democrats often have a self-righteous view of the world, believing that they are, among other things, environmentally superior because they don’t drive as much. It’s an extension of the elitist and condescending view that many political observers believe sunk the Harris campaign.

Urban dog walkers can be pretty smug.

Exurban Republicans, meanwhile, often believe that living in a single-family home and driving everywhere is simply the natural order of things – a way of life that everybody wants. They also want to escape what they see as urban ills like poor schools, homelessness, and crime. (These problems are trumped up, so to speak, by the president-elect, who – despite being a New Yorker – persistently characterizes cities in 1980s apocalyptic terms.)

A good example of the exurban suspicion of urban life is the trope that the idea of “15-minute city” will lead to fencing and surveillance to ensure that residents don’t leave their designated district. This isn’t true of course – the idea is that people should have everything they need in close proximity to where they live – but it’s a pretty persistent conspiracy theory. It goes back at least 15 years, to the whole Tea Party/United Nations/Agenda 21 notion that urban planners wanted to round up suburbanites and force them to live in apartments rather than single-family homes.

And all this suspicion only gets reinforced by geographical separation. If you live in an urban apartment and walk your dog every day, you tend to think that’s how everybody should live. And if you live in a single-family home in the exurbs, you tend to think that’s how everybody wants to live.

Can We Break The Partisan Divide Of Where?

Obviously not everybody wants to live in an urban apartment and walk their dog. But it’s equally true that not everybody wants to live in the suburbs or exurbs.

Public opinion surveys consistently show that about half of the population wants to live in large-lot suburbs, while the other half would prefer to live in smaller houses on smaller lots where they are closer to the things they need every day. (This result has shown up very consistently even in car-oriented Houston, where the Kinder Houston Area Survey has found this result over and over again.) But obviously our communities are not built to reflect this preference; they are mostly built as auto-bound suburbs.

So most people live in the suburbs because they have no choice. I can remember walking single-family neighborhoods back in Ventura, California, when I was running for the city council there, and finding an astonishing diversity of households: empty-nester couples, single moms with kids, nuclear families, multigenerational households, families (mostly Hispanic) living two or three families to a house. Obviously many of these households would have been better off – both financially and in terms of lifestyle – in a different housing situation. But those different situations simply weren’t available.

And the truth of the matter is, especially for people of modest incomes, the suburbs can be dangerous. Many families that live in the suburbs because they have no choice also cannot afford the three, four, or five cars often required for a family to survive.

Suburban roads can be very dangerous to pedestrians, who are often women and children.

Some family members – most often women and children – must engage in treacherous walks, often crossing busy arterial streets, to get where they need to go. It’s no surprise that, for pedestrians, most of the dangerous metropolitan areas in the nation are in the sprawling suburban Southeast. But, of course, this fact just highlights yet another division in our society: the division between those inside cars, who are safe, and those outside cars, who are not.

As the authors of The Big Sort, separation by where is tearing us apart. Is it possible to undo this trend?

Well, yes and no.

Based on the presidential election results, it’s possible that the political wall between urban and suburban areas is breaking down. That’s because Black and especially Hispanic voters are trending Republican.

Because of historic segregation and other factors, Black households are largely stuck in traditional urban areas. As they have moved from poverty into the working class, Hispanic households have also moved into older, low-amenity suburbs where housing is somewhat affordable – but where living without a car is dangerous. Even in the suburbs, these groups are far more dependent on public transit than people who are white and/or more affluent.

And even in 2024, the traditional pattern mostly held. Just look at this map from Harris County in Texas, where Houston is located. The dark blue areas are the traditional African-American neighborhoods. The light blue areas are Hispanic communities. The red areas are where the white folks live.

Presidential election results in Harris County, Texas (Houston). Source: Houston Landing

But the next county-level presidential map may look a little different. You might see Hispanic areas in particular turn up red on the map – just as they did, notoriously, in South Texas this time around. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that people who don’t trust each other because of their political beliefs will move closer to one another. What is means is that people in the same Hispanic households are moving apart politically.

I’m a strong believer in the power of where – the power that attachment to place and proximity play in our lives. And I believe in the public opinion surveys that say more people want to live in more compact, walkable neighborhoods. I also understand the families of all political beliefs wants to live near good public schools. So it saddens me to think that The Big Sort might be permanent – that even if people live more similar lives (Republicans in walkable neighborhoods, Democrats in suburbs), they’re still likely to congregate near one another, creating a 15-minute city that fences them in politically.

So appreciative of the thread of study you are offering in this substack. Keep it up. I'm deeply believe that our cities (and burbs) will experience profound change in the next 5-7 years and you are helping me to think about it.

But I am better because I don’t own a car.